Memoir…Wisdom from my father

The first thing I remember about my dad was his huge, powerful hands. I watched him crush walnuts inside his strong fist at Christmastime when the nutcracker was nowhere to be found—and I figured a man with strength like that could do just about anything.

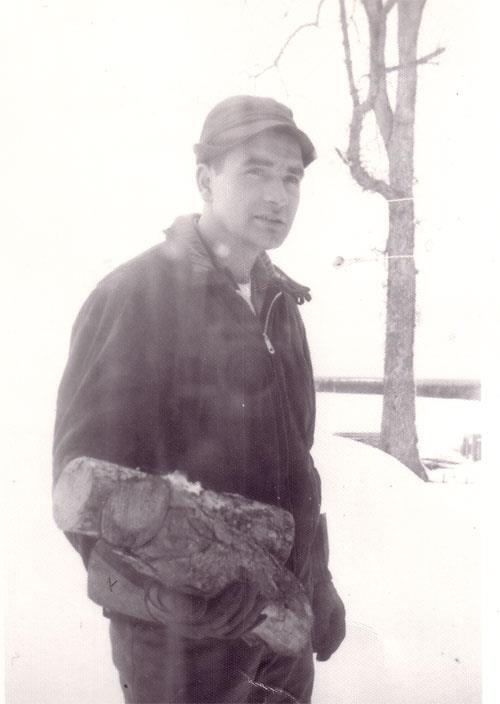

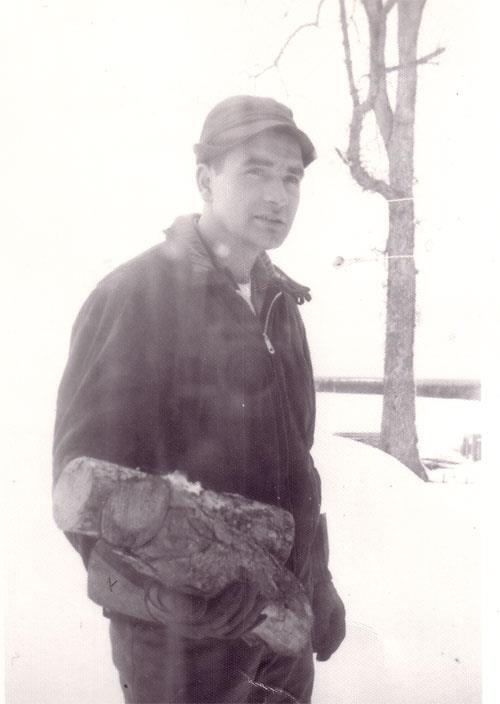

Donald Earl Herrington was born on January 19, 1935 into a large, poor family in rural New Brunswick. His mother died when he was six and his father died when he was fifteen. The ten siblings largely raised themselves. He had a grade three education and began working in the woods when he was nine. He killed his first deer with a .22 when he was twelve—not for sport, but to feed his family.

Learning to survive off the land is probably why he loved the outdoors for the rest of his life and was the most comfortable in the country. Large cities and unfamiliar situations made him nervous, but within his own familiar boundaries, there was nothing he couldn’t do.

Such a traumatic, poverty-stricken childhood makes a person self-reliant. He told me that when he was small, he learned very quickly never to ask for anything and never to expect anything.

My father was more capable than anyone I’d ever known. I believe he had the natural ability to be an engineer, but never had the resources or the opportunity to study. He earned his first real job at 15 (and an apprenticeship) at an appliance repair business. Despite his lack of formal education, he learned his trade well and took pride in it.

Whenever he didn’t know how to do something, he read a book to figure it out. While I was growing up, he worked as a repair and maintenance technician on an air force radar base in St. Margaret’s, close to Chatham. Whatever was broken, he fixed it: from the microwave towers to refrigerators and freezers, to oil-fired furnace boilers. He was comfortable with himself, and liked to be admired. He liked it when people asked his advice or asked him for help.

A couple of personal memories

Every payday, which was every second Thursday, my parents and I would travel to Chatham (now part of Miramichi city) to buy groceries after supper. On one particular Thursday night in the wintertime, we passed one of many dirt side roads on route 11—a poorly-lit rural highway—on the way into town. By six o’clock, it was already dark. We heard a huge thump on the passenger side of my dad’s baby blue Ford van. Something had pelted the side of the vehicle with force.

My father slammed on the brakes and backed into the side road. My mother was aghast and said, “Don, what are you doing?”

“Somebody threw something at us,” he replied, as if it should be obvious. He put the van in park, and jumped out.

“Don!” Mom hissed, trying to get his attention. “You don’t know who’s out there!” He ignored her, slammed the door behind him and gave chase. I sat in the back seat with mouth agape and we both listened for what came next.

Dad followed the scoundrels into the darkness. They were throwing tomatoes at passing vehicles, which we figured out later, because some of the seeds still clung to the side of the van by the time we arrived at the grocery store. (What kind of a stupid game is that, by the way? I suppose that’s what you do for fun when there’s no Netflix.)

My father picked up a rock off the road and pelted it into the blackness.

By sheer luck, he hit one of them. Where? In the back? On the leg? It was too dark to tell, but the number of swearwords that pierced the air told us it really hurt.

Dad yelled back, “That’s what you get for hitting my van, Jack!”

He jumped into the van and drove away, his lips curved in a tiny smile of satisfaction.

From this, my ten-year-old self learned that, a) My Dad must have infra-red vision; and b) under no circumstances do you mess with his Ford van.

He almost never admitted when he was wrong. We joked about buying him a t-shirt with his favourite adage: “I’ve only been wrong once: that’s when I thought I was wrong, but I was mistaken.”

And the one he said to me most frequently, “If you do a little favour for somebody else, they’ll do a little favour for you…” In my mother’s eyes, this meant the garage was always filled with other people’s refrigerators, freezers, ice makers, lawn mowers, automobiles, or any other machine that needed repair while millions of projects around the house remained untouched.

But from his example and my mother’s, I learned to be generous, and to share my talents and time and my money with other people. And I have to say that it’s true: people have been generous with me in return. Even if they are not, it’s a virtue which carries its own reward.

Fatherly guidance

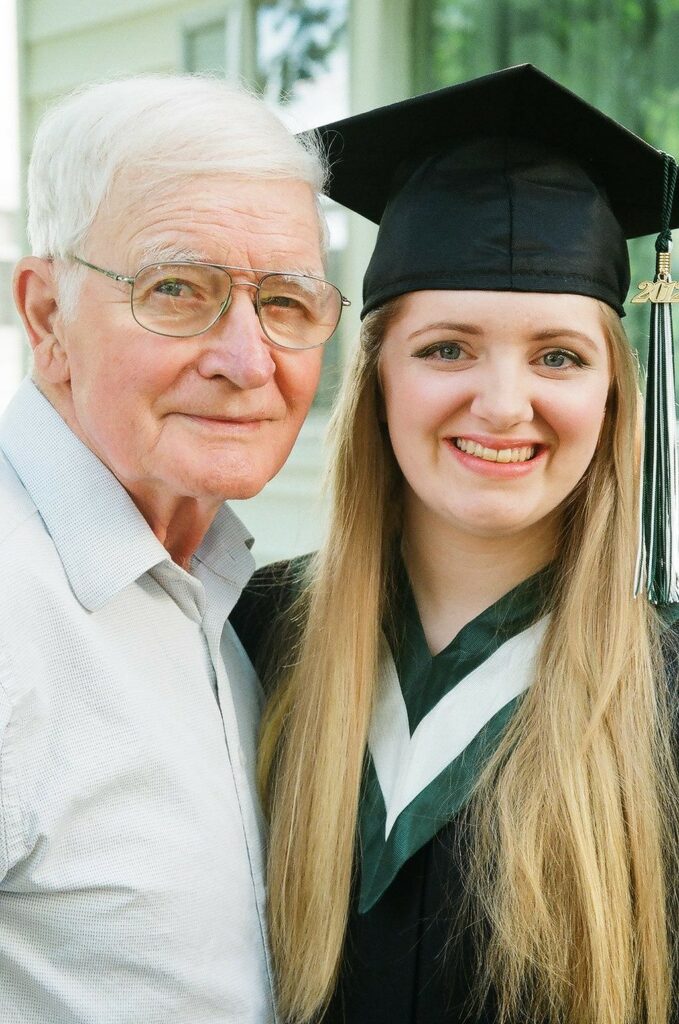

All through high school, I had planned to study marine biology at university and organized my high school courses accordingly. But just before I graduated, I made an about-face: I decided to go all the way to a technical school in Ontario and study public relations instead.

On a subconscious level, I knew I was an artistic person, not a scientist. I wrote my first book when I was 15. Mom was appalled, perhaps because her baby was moving so far away and picked some strange course out of the blue. It was way off the original plan.

But my father’s response was more measured.

One day he sat me down and asked if I knew what I was doing. Now, I have teenagers. This is a ridiculous question to ask them. Don’t all teenagers know exactly what they’re doing? What 17-year-old do you know would ever admit, “Gee, I don’t think I know what I’m doing. Please tell me what I should do and I will follow all of your instructions without question.”

“When I was a young man, I had the opportunity to go into business with my American cousin,” Dad explained. “But I had just been hired at St. Margaret’s Air Force Base and I thought a bird in the hand was worth two in the bush. My cousin ended up being very successful, and in later years I wondered if I had made the right decision. But at the time, I didn’t want to take the risk.”

In his quiet, low-key way, he was warning me about the importance of making all decisions mindfully. Yet, the decisions I feel good about today affect me differently tomorrow. That doesn’t mean that they were wrong necessarily, but it does mean I have to be willing to live with the consequences.

I can still see him sitting on the sofa that day, I in the chair with the flat, square arms across from him. He said, “Some people have jobs that completely consume them. They’re never home, and when they are home, they take their work home with them. I never wanted that. I wanted my nights and weekends to be completely mine. I didn’t want to have to think about work until Monday morning, and I wanted to leave it at work when I came home Monday afternoon.” He fixed his sharp, blue eyes on me and said, “You need to know what kind of person you are and what you want out of life.”

Well, of course, I didn’t. And yet, in a way, I did. I remember thinking, “Aw, isn’t that nice…my Dad’s trying to pass some wisdom along to me…” but I didn’t really grasp the true weight of those words until much later in my life.

Some decisions in life are completely right or completely wrong, but there aren’t that many of them. There’s don’t kill people, don’t cheat on your spouse–I think there’s ten of them, actually–but there are millions of small and medium-sized decisions we make every day that determine the day-to-day course of our lives.

Decisions are like clothing. Some pieces just don’t fit when you’re a kid: you must grow into them. For me, fitting into my father’s confident clothing took many years. In some ways, they still don’t fit the way they fit him. And now that I look at him with adult eyes, I see that his clothing might not have fit the way I thought it did. I see him as a much more complicated person now–A stubborn person with regrets and insecurities.

The hard days

On September 3, 2010, I awoke in the middle of the night after having had a dream about my father. Earlier that evening my family had been watching a movie about Abraham, the father of the Jewish nation. I dreamt I was standing inside my uncle’s house and we needed a sacrifice.

My father went out the front door, which looked like the entrance to a tent, and returned with a live leopard. He was carrying it across his shoulders, and he was desperate to get it upstairs where we would kill it as a sacrifice for God. I knew he had done this many times before, carrying a leopard on his powerful shoulders.

In the Old Testament, the leopard represents the kingdom of Greece…and with it, Greek reason and thought. My father valued reason and intelligence above all things.

In this dream, he kept fighting to keep the leopard motionless, but I could see it was getting the better of him. Though he continued to show the confidence in his own strength that he had always displayed, the leopard forced him down on the ground and closed his huge jaws over Dad’s throat.

While my father continued to struggle, I ran to his side and put my hands around the big cat’s mouth and tried to pull him off. I can still feel his wet jowls and his slimy, yellow teeth between my fingers. I was powerless to stop what was happening. I was desperate, and thought that I needed a knife to thrust into the leopard’s neck, but I didn’t dare let go. Then I woke up and, sitting straight up in bed, I knew I had just dreamed something significant.

A few weeks later, Dad was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. It was his first brush with mortality. He had always been rugged, capable, resourceful and rarely ill. He loved the outdoors, loved fishing and hunting and camping and tramping about in the woods. He loved building and creating things with his hands. Trailers he welded himself, a houseboat he built out of F-18 aluminum fuel pontoons, a cottage bathroom built with a split cedar lighting pole. Our yard was always a graveyard of spare parts and machinery. And lots of duct tape.

But by the age of 75, the man who was still cutting 10 cord of wood every spring to burn for the winter was shocked to discover that relying on other people would soon become a way of life. He denied it. He was a difficult, angry patient. Doctors diagnosed dementia and Parkinson’s. They took his driver’s license, and forced him from his house and his precious family land and moved him to a facility in 2016.

His resentment never waned. He would have much rather had a stroke while chopping wood or while driving his four-wheeler to his 1930s family log cabin, and I wish for his sake that he’d had his way.

But life is not fair. We don’t always get our way. Instead, he withered in slow motion.

In Ecclesiastes, Solomon writes, “Remember your Creator in the days of your youth, before the days of trouble come and the years approach when you will say, “I find no pleasure in them.”

The days of trouble came for Dad, but what made it worse was how shocked he was. He had always relied on his great strength, and it served him his entire life. How well my dream describes his tenacious final days, which extended far beyond what anyone expected. The oft-repeated phrase I heard from medical staff was, “your father still has really strong hands.”

All strength wanes eventually, and his experience tells me that I can’t control the future. I can only control what I do with today. So I intend to concentrate on the things that matter to me now, because if I’m so fortunate as to grow old, I may not have a say by then. And I trust the God who made me—therefore I don’t fear the future.

I have decided not to remember the angry, irrational man of the last few years. Dad certainly wouldn’t want me to. The dreamy image of my father coming into my uncle’s house is how I will always remember him, and how I would like you to remember him: a man who was strong enough to carry a leopard on his shoulders.

Beautiful. I will always, ALWAYS remember your Dad as the smiling, bear-hug giving man he was.

This is a magnificent story, written with such beauty too!

This is a beautiful tribute to your Father. He must have been an amazing man. Thankful that he is at peace now and has regained his full strength once more. God bless!